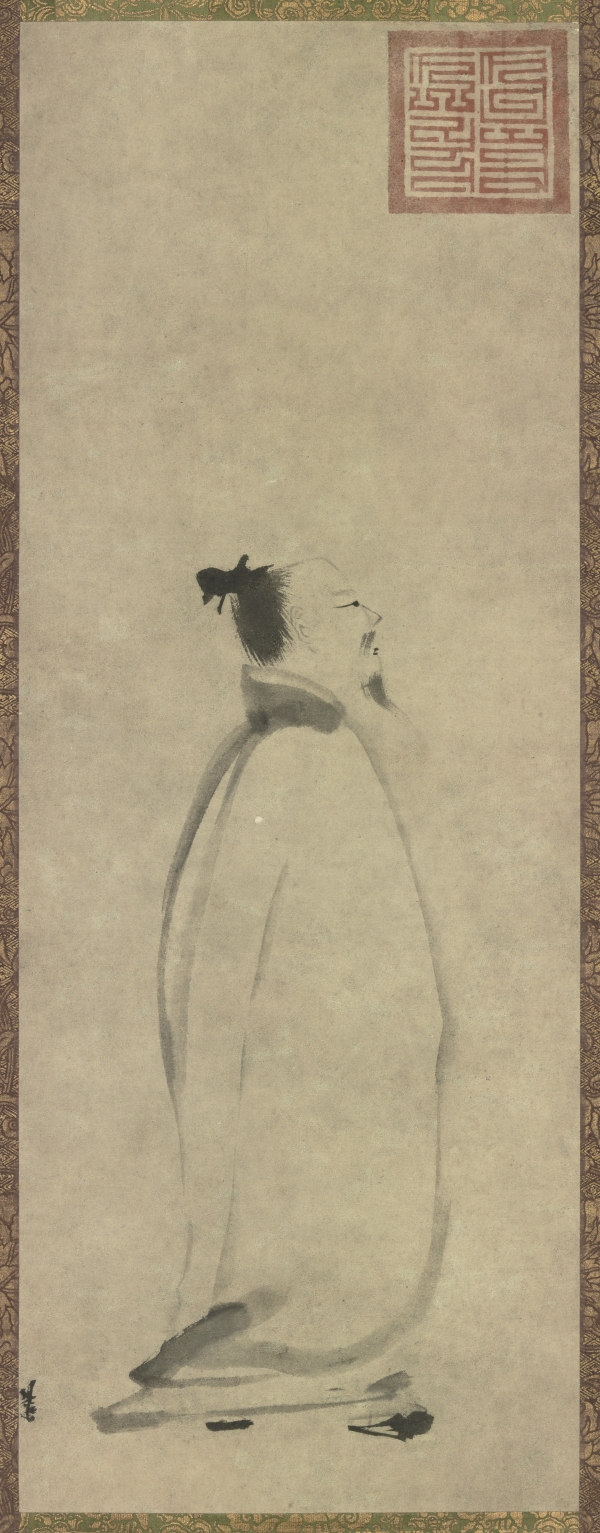

In the 7th century, during the Tang Dynasty of Empire China, there was Li Bai – one of the most prominent scholar and poet in Chinese culture – who watched the bright moonlight during his far-away-from-home journey, and composed his famous poem “Quiet night thoughts” (Chuang Qian Ming Yue Guang):

“Bright moonlight before my bed

I suppose it is frost on the ground

I raise my head to view the bright moon

then lower it, thinking of my home village.”

(Translation from https://eastasiastudent.net)

Li Bai composed these beautiful words when he was detaching from his homeland for the duties assigned by the Emperor of China (in modern and scientific term, he was an assigned expatriate in the ancient Chinese context). Typically, during this era, these types of journey lasted for an extended period (usually for years or decades), and this poem specifically expressed Li Bai’s reminiscence of his left-behind hometown. This legendary poem is perhaps one of the first written documentation about the concurrent connectedness between individually mobile people and the lands that they have experience with.

Transnationalism, by definition, is the process where people sustain their ties and belongingness across borders and geographic locations (Faist, 2010). It goes beyond the “homesick” phenomenon and captures meaningful connections between people and various geographic locations where they travel over the course of their lives. Transnationalism has been extensively studied in some scientific areas such as sociology, political science, and geography. The most prevalent topics are properly the transnational identity of migrants, and their social embeddedness while abroad (Beaverstock, 2002; Ryan, 2018). There is no doubt that migrants or expatriates are generally transnational agents. This is hard to believe that when moving across countries, they can completely forgo what they left behind. The simultaneous belongingness may occur not only among migrants’ or expatriates’ homeland and their host countries but also with numerous other countries – depending on how much mobile and embedded they are.

In management field, there are unfortunately insufficient research about the transnational character of expatriates or working migrants even though it has been addressed as different terms such as “dual embeddedness” (Froese, Stoermer, & Klar, 2018) or the embeddedness in home-, and host country (Lo, Wong, Yam, & Whitfield, 2012). Scientific evidence proved that understanding expatriates’ and migrants’ embeddedness is important to understand their behaviors and outcomes. For instance, the “dual embeddedness” is especially beneficial if the expatriation is meant to promote knowledge transfer between the company’s head-quarter and its subsidiaries (Froese et al., 2018; Wang, 2015). Furthermore, knowing expatriates’ motives to move abroad, we may understand why some of them, despite the deep connections with their less-developed homeland, tend to commit to their employment abroad (Lo et al., 2012). In this case, transnational embeddedness is a crucial motivator for their retention in host organization because it ensures that expatriates can continuously support their important people or values back home.

It has been observed over the years that tools and conditions to sustain the connections with homeland can be important for expatriates. For instance, many favor the flexible working policies that allow them to visit hometown regularly or at least in some important traditional events (Ryan & Mulholland, 2014). Knowing this preference, HRM/ Global mobility managers, and immigrant policymakers can tailor their practices for foreign employees to cater to the immigrant-friendly perception and organizational affective commitment. For instance, some countries have implemented the law in which expatriates are entitled to have additional holidays in accordant with their original cultures such as Home National Independent day and traditional New Year day (Vietnam Labor Law). The acknowledgment and effectiveness of transnationalism-promoted practices, however, still require future research.

This is necessary for both scientists and practitioners to focus on transnationalism of expatriates or migrant workers in the future. Meanwhile, before any scientific evidence may arise to support practical policies, transnational phenomenon has been naturally existed alongside the history of human migration.

References

Beaverstock, J. V. (2002). Transnational elites in global cities: British expatriates in Singapore’s financial district. Geoforum, 33(4), 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(02)00036-2

Faist, T. (2010). Diaspora and Transnationalism: What Kind of Dance Partners? In R. Bauböck & T. Faist (Eds.), IMISCOE research. Diaspora and transnationalism: Concepts, theories and methods (pp. 9–34). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Froese, F. J., Stoermer, S., & Klar, S. (2018). The Best of Both Worlds: The Benefits of Dual Embeddedness for Repatriate Knowledge Transfer. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2018(1), 17301. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2018.17301abstract

Lo, K. I. H., Wong, I. A., Yam, C. M. R., & Whitfield, R. (2012). Examining the impacts of community and organization embeddedness on self-initiated expatriates: the moderating role of expatriate-dominated private sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(20), 4211–4230. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.665075

Ryan, L. (2018). Differentiated embedding: Polish migrants in London negotiating belonging over time. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(2), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341710

Ryan, L., & Mulholland, J. (2014). French connections: the networking strategies of French highly skilled migrants in London. Global Networks, 14(2), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12038

Wang, D. (2015). Activating Cross-border Brokerage: Interorganizational Knowledge Transfer through Skilled Return Migration. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(1), 133–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839214551943

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.